Sensory Spaces Raphael Refti

Client: Museum Boijmans van Beuningen

Purpose: Documentation and editorial

Location: Rotterdam, Netherlands

Hole Two

Hole One

Hole Eight

by Piet de Jonge

I am standing high above the water on the narrow footbridge of a crane. The blue railing could obviously use a coat of paint. There’s a bit of rubbish on the bridge but I am looking straight ahead, to the other side of the water. Night has just fallen and the lights in the harbour have come on. Bright work lights accentuate a red ship that is surrounded by a couple of large yellow cranes. The blue light coming from the business across from me is reflected in the Maas. To the right of it, two lights cast long green lines on the calm water. From the platform, I can see the harbour of Rotterdam in harsh, brightly coloured lights. The horizon shines, proof that work is still going on there. Here on this footbridge, in the dark and some 40 m up in the air, I feel the magic of this place.

The harbour of Rotterdam is an intangible entity, difficult to describe or portray. The tremendous extent of the area could perhaps be indicated with an aerial photograph or on a map, but then all of the particulars would be lost. Detailed shots of ships, containers, machines or cranes are the other extreme, but they cannot capture what it’s all about, either. Portraits of harbour workers or directors or members of the board might make great pictures, but when it comes to capturing the essence of the harbour? No.

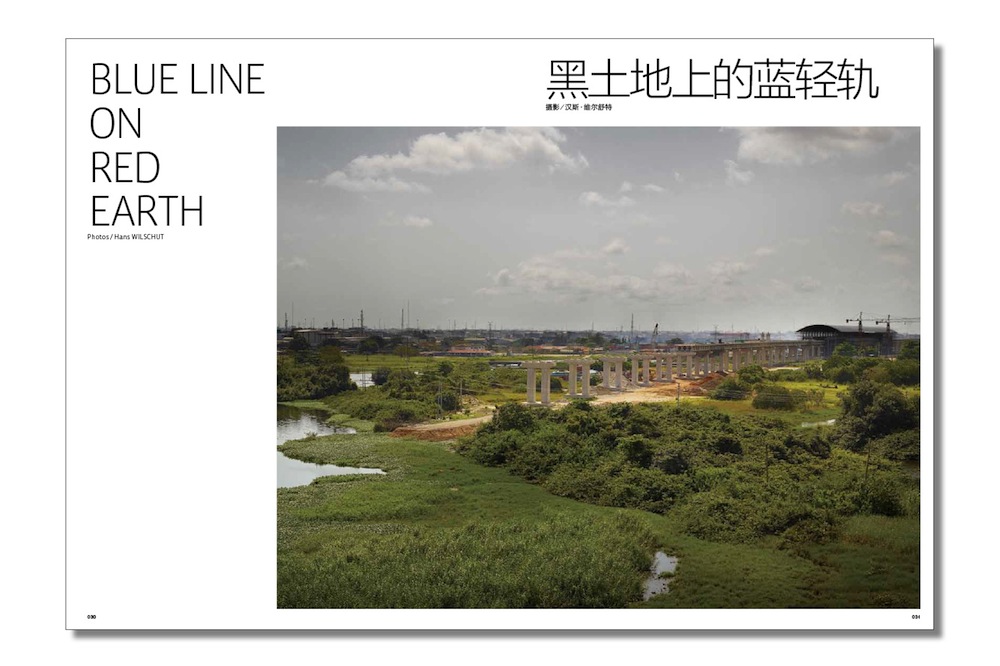

At the beginning of 2009, the Port of Rotterdam Authority asked Hans Wilschut to make a series of photographs about the Rotterdam harbour for their offices on Wilhelminakade. The commission gave the artist complete freedom to do as he pleased, with the understanding that this would build upon his previous work. For some ten years or more now, Wilschut has been fascinated by urban landscapes. In the photographs he takes of major cities, architecture would appear to be the central theme, yet the actual subject of his work is mankind, mankind as the maker of our own environment. Wilschut shows the results of human activity. Sometimes this produces unpleasant images, such as the ruins of an apartment building that collapsed as a consequence of the contractor’s fiddling with permits. But his often large-scale photographs primarily portray the massiveness and impersonality of the environments in which millions of people live.

In order to clearly demonstrate the expanse of such urban areas, he chooses high vantage points, usually the roofs of tall buildings. Using a technical camera, he captures the last glow of the setting sun mixed with the artificial light coming from areas inhabited by people. It is unimpor-tant to him whether a city is in Asia, Africa or America. His photographs show that people live in a different world nowadays than they formerly did. By photographing different places around the globe, he shows that cities are beginning to look more and more alike a veritable global community. Wilschut considers it his task to record whatever he encounters that fascinates him at a certain moment. He exerts an influence on reality by his choice of vantage point and time of taking the photograph, and by the use of modern equipment and computer techniques. These elements also enable him to give his work an extra intensity. For Wilschut, the Port Authority’s commission was in line with this way of seeing the world; he approached the project by asking himself: What is the secret of the harbour?

I am again standing on a crane, this one dating from the 1960’s. Ahead of me, I see a colossal blue engine hall. Beneath me, I see the roofs of a number of industrial buildings. One of them is rather overly green, the only roof that is covered with moss. The sun has gone down, its last light reflecting against the clouds, which in turn give the water a purplish red glow. The puddles on the ground betray the fact that it has rained hard recently. As a result, the air is so clear that I can even see the cables of the broadcasting mast straight ahead. The light enchants me. You could even call the view fairylike if it weren’t for those enormous storage tanks and the petrol chemical complex that are such a harsh reality in the background. Below me to the right, steam billows up in a white cloud.

Wilschut drove with his camper from Rotterdam to the Maasvlakte. He followed the harbour along the river and kept being blocked by fences that surround business premises. He soon realized that these places inaccessible to the public offered the most challenge and decided that this was what he wanted to photograph, especially because here he could find the high vantage points needed to convey the vastness of the area“ not tall apartment buildings this time, but chiefly large cranes and high smokestacks. Wilschut gradually developed the idea that these places that are off limit to ordinary people were in fact the real essence of the harbour. With the Port Authority’s commission in his pocket, he approached a number of companies to ask whether he could take photographs for a sketch proposal from the top of a crane or a high platform.

After looking at the test shots, he realized that he was doing what he finds most interesting: taking surveys of areas he doesn’t fully understand.

Before me lies a vast terrain with containers. Moored at the wharf are a few ships still piled high with those giant metal boxes. On the wharf stands a regiment of hoists that have brought earlier loads on land. The terrain has a grid work of rails over which the containers can be moved by means of huge electromagnets. Because of the crisis, the terrain is fuller now than ever. Whereas before this, ships had to wait to be unloaded, now cargos must wait for ships to take them away. The high streetlights bathe the terrain in a golden light, intensifying the colour of the blue paint on the metal loading platforms and containers. The French call this time of the day l’heure bleue, the blue hour: the moment that dusk arrives, when daylight slowly fades away but it is not yet really dark.

With the photos that he had now taken, Wilschut had an easier time of convincing other companies to give up their initial resistance to letting a photographer take pictures on their premises. Yet it often cost him two or three months to receive permission, and especially to convince security guards of the necessity of letting him take photographs at precisely the place and time he desired. Over the period of a year, Wilschut succeeded in penetrating further and further into the harbour’s hidden areas. He developed a special acquaintance with corporations such as emo, the biggest dry bulk terminal in Europe; the shipyard and offshore operations of Keppel Verolme; the Europe Container Terminals; but also Vopak, Aluchemie, and petrochemical industries such as Argos Oil, ExxonMobil and Shell. He discovered the advantages of globalization: a crane that hoists a container onto a ship in China must be the same as a crane in Rotterdam. In order to function as a multinational, standardization is essential.

Between huge mounds of iron ore and coal runs a long straight road with a conveyor belt alongside it, apparently extending to the horizon. The gigantic yellow monster that I am standing on is brightly lit and rides slowly, but with jolting movements, towards the silos at the end of the street. The dimensions are overwhelming, the distances appear endless and the quantities immeasurable. It looks like a scene in a sciencefiction film. The tops of the artificial hills are dark silhouettes against the evening sky. In the distance, you can see the cranes that unload the ships and bring in more commodities. Despite the crisis, the company is having a peak year, because money is now being earned from the storage of cargo in the harbour. I ride further along the road, guided by the lights next to the conveyor belt.

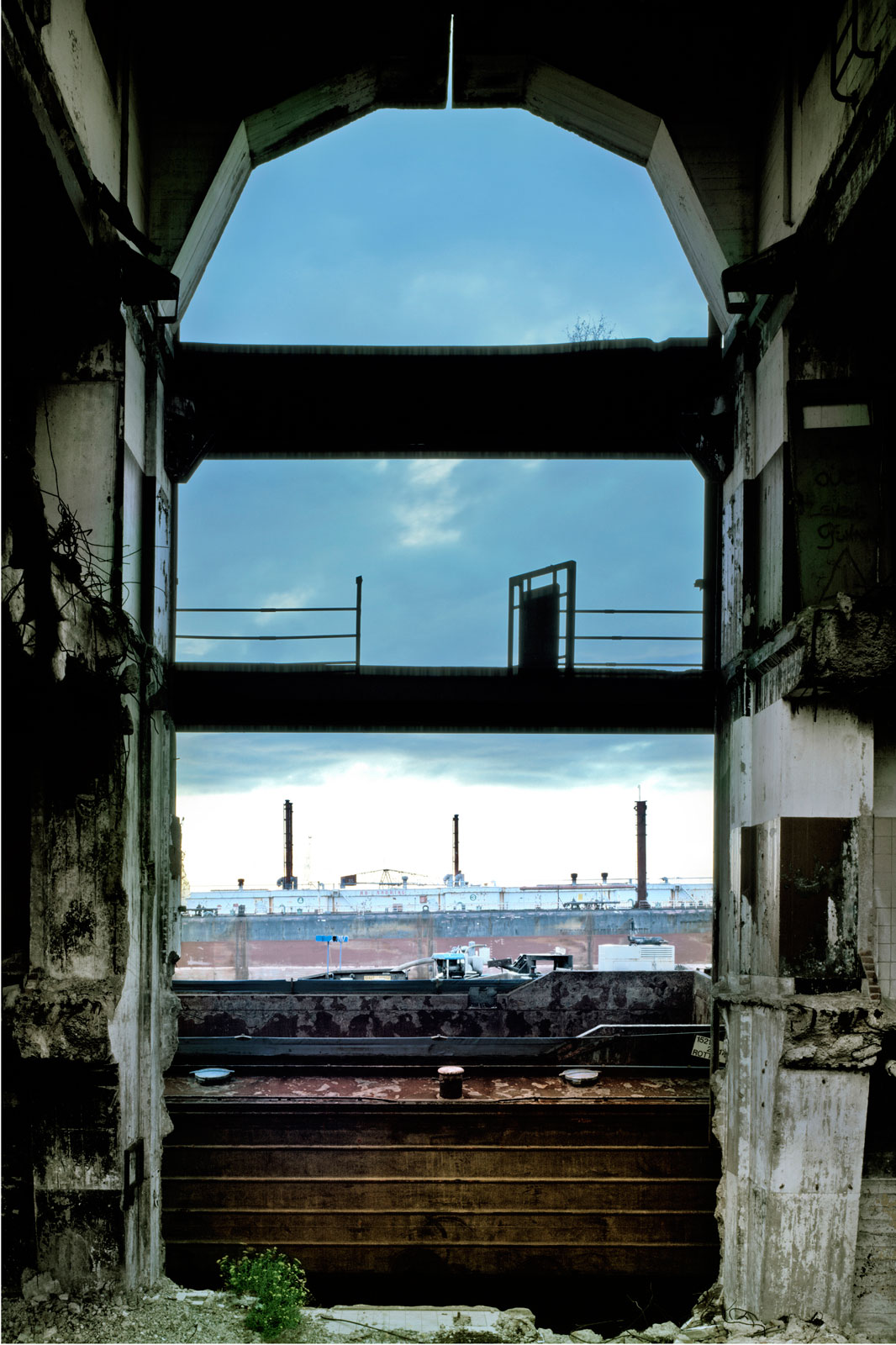

Wilschut gradually got a better idea of the area and a growing understanding of the difficulties of photographing the Rotterdam harbour’s industrial landscape. He drove around in his bus in order to experience locations under different conditions and says that during that period it seemed that he was constantly on the lookout for little balconies. For he had discovered that in addition to the fences that surround the terrains, there are also very many railings and fences at higher levels. They came in very handy for him as a photographer, and ultimately became the visual constant in this project. He used the constructions on platforms and footbridges in the foreground of every photograph as a visual introduction to the terrain lying behind them. In this manner, he tried to capture the industrial panoramas of Europoort, the Botlek and the Maasvlakte. No really high vantage points were to be found in the old Rotterdam harbours, so there he could not get the overview that he needed. It was necessary to be far away from his subject matter because he wanted to portray it as a universal harbour. By avoiding recognizable details such as the Euromast, the Erasmus Bridge and the SS Rotterdam, Wilschut prevented his pictures from becoming topographical anecdotes.

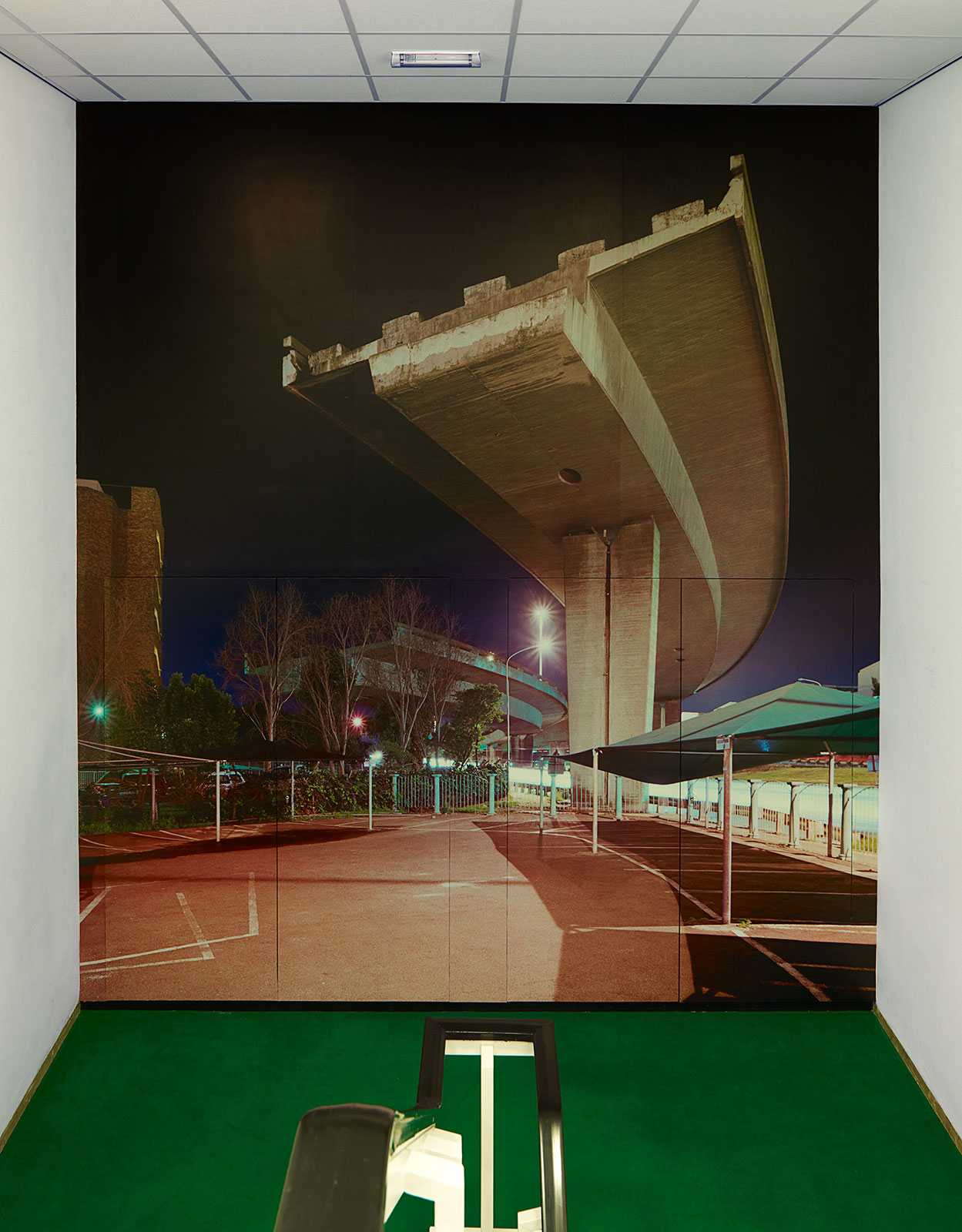

The project that he ultimately made for the Port of Rotterdam Authority consists of 17 photographs that are printed on canvas and framed in boxes lit by led lights. These light boxes are mounted in as many lift waiting areas. They are as large as the end wall (256 x 355 cm) of the space in which the six lift doors are situated. When visitors come out of a lift, they see one of the enormous photographs, in which the railings always form a link between the viewer and the landscape. Wilschut uses pipes and beams with their at times bright colours to lead the viewer across various terrains along the river: a container depot, a conveyor belt for iron ore, or the new air purification system of an aluminium factory.

The streetlight right above me on the fire escape has not yet gone on. I have just seen the sun setting and have also seen the lights on the terrain slowly coming on. The large streetlight I am standing under is mounted on top of the roof, so it will take a few minutes before the sensor turns on its sodium vapour lamp. The thick pipes of the enormous installation are still new and have a silvery glimmer in the bright light. Hanging in the air are dark purple clouds that are more reminiscent of an American Western than a Rotterdam industrial terrain. In the meantime, I am amazed by that little tree standing over there, looking so forlorn among all that metal.

Wilschut took almost all of his photographs right after sunset. He uses this moment, when there is a particular mixture of daylight and artificial light, because colours gain an extraordinary intensity at that time. Clouds lose their mass and become silhouettes, dramatically backlit by the last rays of the sun. By photographing each of the terrains at the same moment of the day, he creates a unity between the various subjects. He is well aware that he makes free use of aesthetics, but he does this in order to show people things they normally would never notice.

A walk through the Port Authority building confirmed this. Employees entering and exiting the lifts were all enthusiastic about the photographs in the building and said that they are proud of “their” harbour. They see familiar places in an unfamiliar way. The railing at the foreground gives you the feeling that you are really standing in the harbour and that you could turn around and look in the other direction. When you see the businesses in the photographs, you know what sounds go with them. These sorts of association come up because Wilschut gives his images such a keen intensity.

Wilschut is looking forward to the last photograph he plans to take for this assignment. He knows exactly what vantage point he needs to conclude his project. The only problem is that it does not yet exist. Although 139 million m3 of sand have been raised in one year’s time, the second Maasvlakte has not yet been completed. A special crane was developed to make a dam wall out of blocks of basalt measuring 2 m3. They come from an old dike that is no longer in use and smell of mussels and seawater. The crane is constructed so that the blocks can be deposited very precisely. Called Blockbuster, it is a brilliant blue and has yellow railings. Wilschut thinks it would be terrific to take a photograph of the newest part of the Netherlands, the newest harbour, from the top of that particular crane, far off shore, and with such a fine yellow railing in the foreground.

by Bas Heijne

Distance and engagement in Hans Wilschut’s photographs, these emotions cease to be each other’s opposites. Time and again, he seems to step back, deliberately removing himself from the scene, precisely in order to come closer, to pierce to the core, to see even more acutely. He avoids our gaze, emphatically refusing to take our perspective. He is the outsider who compels us to look again, who infuses the banal and deathly world with unanticipated new life. His work deliberately heightens the tension between the outsiders perspective and his engagement with the world around him.

This tension is well known to us, like a thread running through the history of art.

About two thirds of the way through Dostoyevsky’s novel The Idiot (1881), the story is interrupted by a passage that might be called an intermezzo, were it not so disturbing. Ippolit, a young man in the terminal stage of tuberculosis, with death written on his wasted features, reads what he calls an Essential Explanation to the assembled company, among whom is Prince Myshkin, the ‘idiot’ of the title. In his confused, emotional outpouring, the dying Ippolit rails against the prince’s attempts to lessen the pain of his final days by caring for the young man in his country home, so that he can draw comfort from the beauties of nature. Ippolit seems to consider this prospect a cruel humiliation: “What use to me is your nature, your Pavlovsk park, your sunrises and sunsets, your blue sky, and your contented faces when all this endless festival has begun by me being excluded from it”(translation by Constance Garnett).

The truths that young Ippolit utters are harsh ones. This parting leaves no room for consolation. The dying man is a protest against the world itself, which has casually distanced itself from him.

Dostoyevsky’s idiot, whom he sees as representing the ‘truly good man’, is deeply distressed by the accusations of the dying boy, who follows his long speech with a clumsy suicide attempt. His ranting reminds Myshkin of a similar feeling of alienation that he once had when under treatment in Switzerland. One brilliant day, the prince had been walking in the mountains, admiring the sun-drenched landscape, when suddenly he felt terribly distressed. He extended his hand to the ‘infinite blue’, as the tears ran over his cheeks. ‘What tortured him was that he was utterly outside all this. What was this festival? What was this grand, everlasting pageant to which there was no end, to which he had always, from his earliest childhood, been drawn and in which he could never take part?’

The emotion is as extreme as it is familiar. Prince Myshkin is the eternal outsider, the man who feels that he plays no part in the world around him. Dostoyevsky’s entire novel can be read as his attempt to connect to the world, to make contact with the things he sees around him, to take part in ‘the human community’ an attempt that is doomed to failure.

But society needs him, and that is the other side of the story. Precisely in his role as an outsider, the prince becomes a kind of conscience of the community from which he is excluded. For the other characters in Dostoyevsky’s novel, Myshkin ‘the holy fool trying to find his way in the world, stumbling toward his tragic fate’ figures as a moral force that lies beyond their reach, by turns admired and hated, praised and derided, but never to be denied. He moves among them, brushes up against them, but is not one of them. His inability to be part of their community is, in fact, his strength.

This theme ‘the outsider with the potential to regenerate a morally debased society’ has enormous resonance in art, reverberating throughout the nineteenth century. For the composer Richard Wagner, it swelled into an obsession. Wagner’s operas, from Der fliegende Holländer (1843) to his final work, Parsifal (first performed in 1882, a year after the publication of The Idiot), always revolve around a man doomed by fate and his origins to stand outside the conventional order, and a community yearning for redemption.

The Wagnerian outsider ‘whether he is the Flying Dutchman, the mysterious knight Lohengrin, the Minnesinger Tannhauser, or the aspiring Meistersinger Walther von Stolzing’ needs the community in order to realize his full potential, or even, like the Dutchman and the Grailseeker Parsifal, to find redemption. At the same time, the community is consciously or unconsciously in search of the outsider who brings the hope of a new and better life. Every one of Wagner’s operas could be seen as a renewed attempt to achieve the impossible: the individual as an artistic and religious force, searching for a place in human society. Only at the end of Wagner’s last opera, Parsifal, does redemption finally occur, when the ‘holy fool’ Parsifal brings the Spear back to the Grail. The outsider and the community come together. No longer is there any distance between them. This utterly divine conclusion was soon recognized, by Friedrich Nietzsche, as a sublime lie, pseudo Christian in character, as seductive as it is treacherous.

In reality, the tension between individual and community remained unresolved. For in the final analysis, all the artistic parables about lone outsiders and communities longing for redemption expressed a basic human truth: at some point, a group or society always becomes lost in its own world, unable to see or alter itself, in need of an outsider to bring about change. At the same time, a free individual is always in search of something larger than himself with which he can identify a community.

In nineteenth century novels and operas it is often the solitary artist ‘the poet, the painter, or the sculptor’ who represents the outsider, the man of superior in-sight. Because Christianity had gone into irreversible decline, the desire for transcendence was transferred to art, which was expected to take over the role of religion. The artist was prophet and Christ in one, an isolated figure, often misunderstood and mocked. Great art held out the promise of redemption, even if it was only redemption in this world.

The great artistic pioneers of the nineteenth century were also the great tragic failures, the holy fools who beat their heads against the wall of reality. The adolescent Rimbaud used his art as a battering ram against the social order. In his ‘letter from a seer’ to his teacher Georges Izambard, he wrote without a shadow of a doubt: “Now I lead as debauched a life as possible. Why? I want to be a poet, and I am working on becoming a seer”. The point is to reach the unknown through the derangement of all the senses. The suffering is tremendous, but you have to be strong, a born poet, and I have discovered the poet in myself.

When he saw that his poetic assault was doomed to failure, he abruptly stopped writing poetry, began wandering the world, and spent his final years as a trader in East Africa. He was still an outsider, but without any vision of renewal. All he had left was a radical loneliness.

The two other legendary loners of Rimbaud’s day, Friedrich Nietzsche and Vincent van Gogh, strove (each in his own way) towards a radical transformation, Nietzsche of the moral order, and Van Gogh of the dominant visual order. Both ended in despair and isolation. All three men combined a drive for radical innovation with an intense desire for community, followed (at least in Rimbaud’s case) by violent rejection. Yet even though they themselves saw their all consuming struggles as unsuccessful, later generations have viewed their tragic defeat as the very proof of their genius.

While they may not have changed the world in any lasting way, they did brush up against it. With their gaze, their words, their visions. The world was not made new, let alone redeemed, yet it would never be the same again.

The mythical proportions that their lives later assumed, and their efforts to transform society permanently, from the outside, created an image that has remained potent in our culture: the artist as the necessary outsider.

For a long time now, we have no longer expected our outsiders to believe in radical transformation. That would strike us as absurdly pretentious. Art has no power over the world. Attempts to make a real impact, to achieve true change and renewal, almost always give rise to impotent bombast, shortlived spectacle, and superficial sensationalism. Artists’ attempts to escape the isolation of the gallery and museum and ‘at a different level’ to escape the distance created by form, can be seen as an extension of the idea that art can bring new life to a society. Public space itself becomes a work of art; the distance between the work of art and the public is eliminated; and the viewers become part of the artist’s vision. They are forced to consider their relationship with the world around them from a new perspective. Public art of this kind can give rise to playful and eye opening experiments, but it is reasonable to wonder whether it truly closes the gap between art and the world. It may solve the problem of space, but not that of time; most such projects are limited in duration. Ultimately, the work of art is a performance that comes to a close. Its effect tends to be merely that: an effect.

Unlike socially engaged art, the work of Hans Wilschut aims for distance. His photographs -including those of the port of Rotterdam- are always taken from an almost impossible angle, a position that we could never take ourselves. His vision is emphatically not our own.

His pictures also emphasize distance in a different sense; in his urban land-scapes, there is not a human being in sight. This is not to say that they seem depopulated. Distance, in this case, is not disengagement, and Wilschut’s cityscapes are anything but hushed. In fact, the distance maintained by the photographer makes us conscious of the continual motion around us, the manic activity that devours our lives. The presence of the human is palpable in all these photos. Everything in them was made and manipulated by human hands. Everything is in motion.

You might well call it a formidable reversal: Wilschut confronts us not with ourselves, but with the things we have created. His photographs show us just what we are up to a unique experience, since the fact that we are part of the world around us, absorbed in our activity, normally rules out any form of supervision. Day after day, we worry about society, writing opinion pieces, watching televised debates, but we are barely able to see ourselves. On the contrary, more and more words and images stand between us and the world. The harder we work to influence our society, the less capable we are of truly seeing it. And as more and more world washes over us, we are less and less capable of seeing that.

What Wilschut has in common with his nineteenth-century predecessors is that his art is a confrontation with society. His work demands consciousness; it wants to have an impact in the world. But he does not seem to be in search of radical renewal. We find no social protest, no humanistic appeal to our sense of responsibility for others, and no recriminations for the mess we so often make in the name of civilization.

His subject is more distant and, at the same time, more fundamental: it is our relationship with the world around us. Hans Wilschut defines community in terms of common property: look, this is what we have made. And the extraordinary thing about his work is that, precisely because his pictures are devoid of human presence, he achieves in a new way what art has so often sought to achieve a new relationship between the individual and the community. For here lies the paradoxical power of distance in Wilschut’s work: the things we have made, our highways, cranes, and highrises, storage centres, conduits, and containers, ultimately show us our own image.

Our distance from the world, which drove Dostoyevsky’s prince to such despair, has now been eliminated. All of a sudden, distance and engagement are one. Our vision is renewed. We see ourselves.

* translation Lourens Reedijk

text Bas Heijne translated by David McKay

Curfew

Port of Prosperity

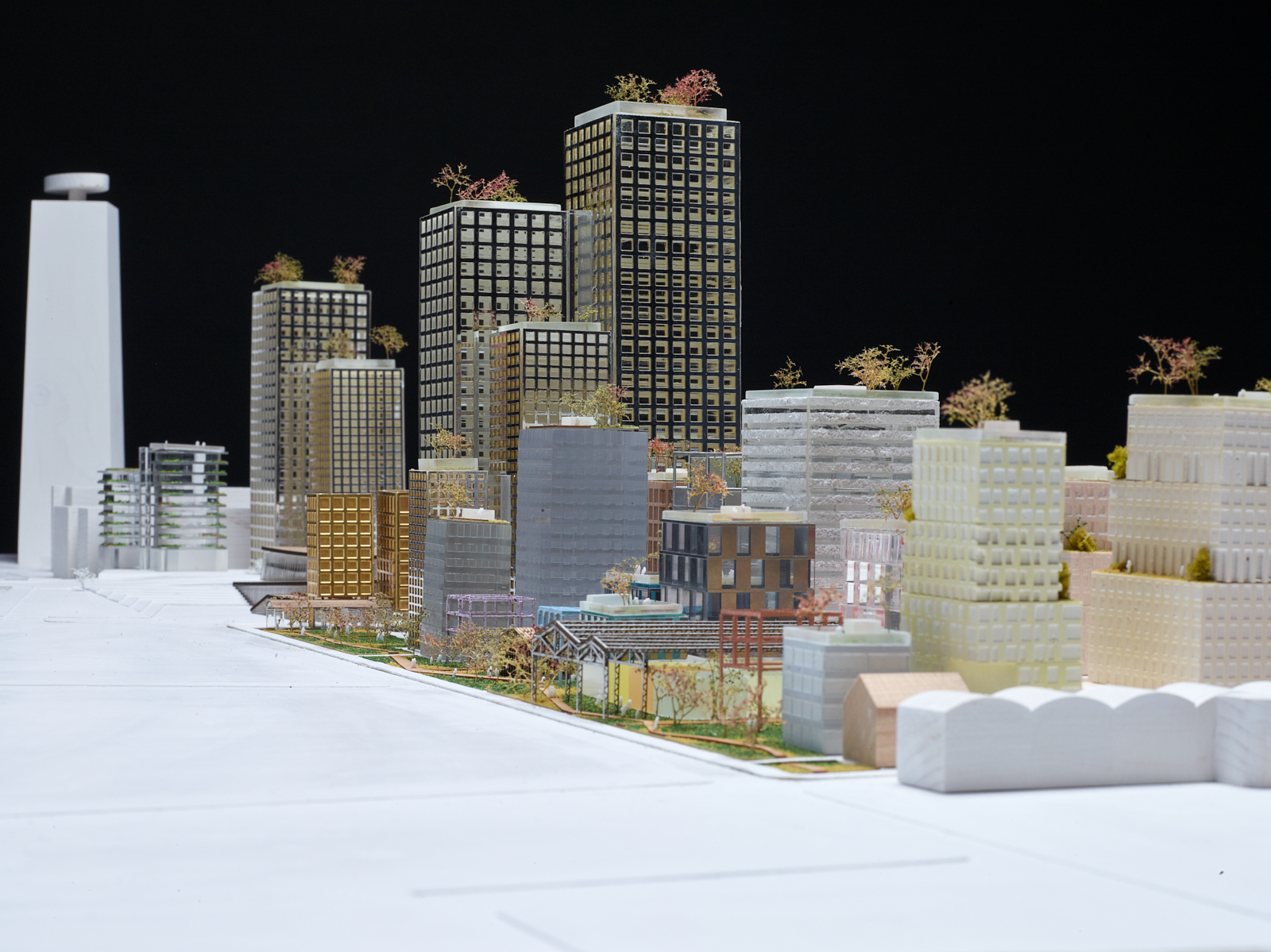

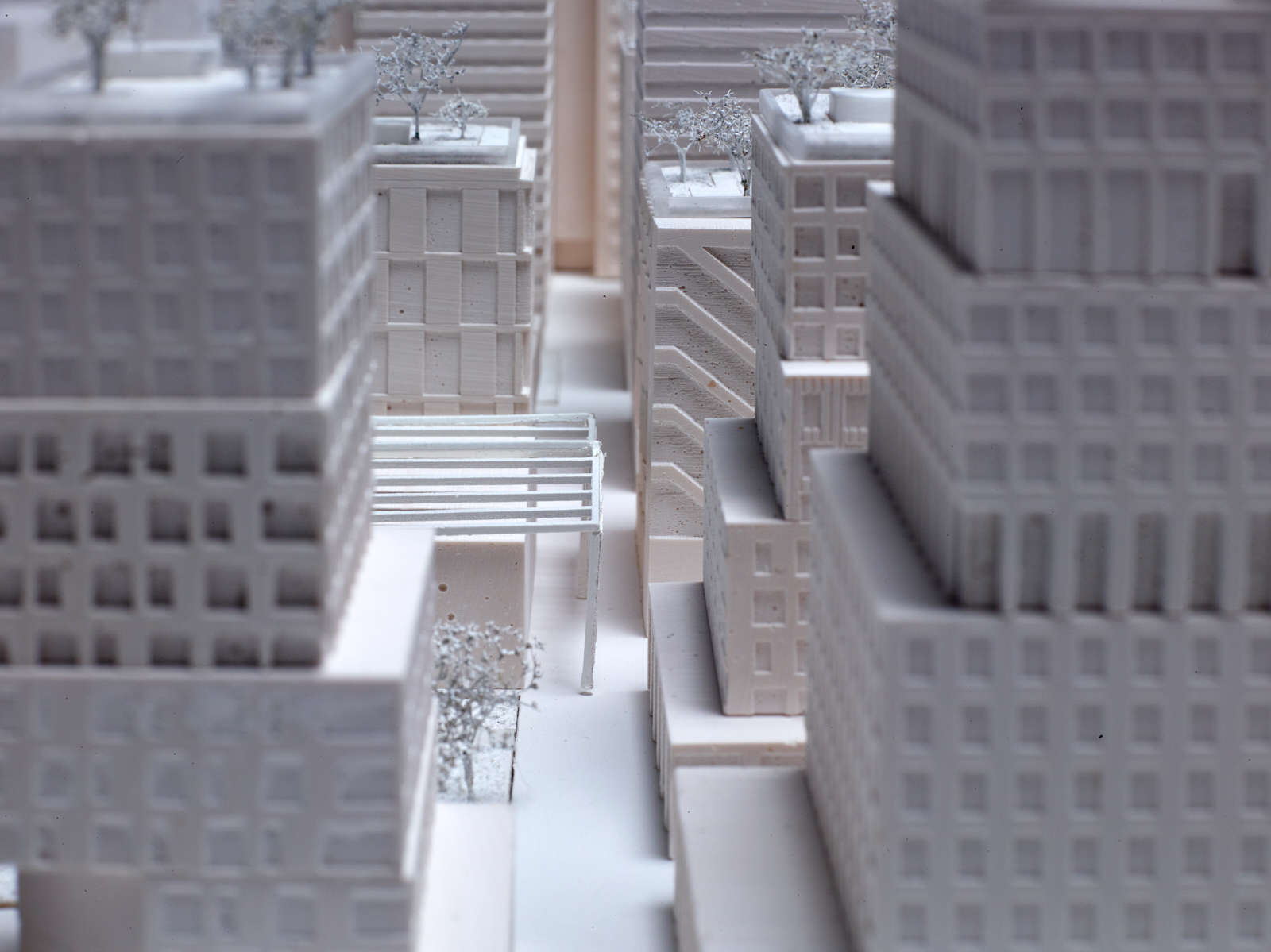

Client: Barcode Architects

Output: Editorial

Location: The Muse, Amsterdam

Windmill

Trunksale

Way Out (station Hoek van Holland Beach)

Beercanal

Set

Shelter

Hidden

Roof

Pit

Institute

Off Stage

Dike

Curtain

The Approach

The Crossing

The Hide Out

Mile 2

Express Way

Ruin

Square

Plan

Limit

Green

Drama

Curve

Bridge

Axis

Avenue

Arbor

Heat

Collectors

Community

Storeys

Scenery

Pylon

Puddle

Pier

Gate

Canal

Isle

Uden

Zaandam

Maassluis

Rotterdam

Leiden

Maassluis

Katwijk

Gorinchem

Seedling

Ajax

Oirschot

Tree Scene

Delft

Amsterdam

Tilburg